Kusu Island Keramat, Singapore

Display of Alan Elliott’s photographs taken in 1950,

with credit to Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge

With appreciation to the keramat caretaker for the stories shared

[This version has been edited to remove the name of the caretaker.]

The Datok Kong shrine. Note the old cloth signboard, with the Chinese characters 那道公 (Mandarin: Na-Dao-Gong; Hokkien pronunciation: Na-Toh-Kong) in calligraphy, possibly a Hokkien transliteration of Datok Kong. Most visitors to the keramat back in the 1950s were of a Chinese-educated background, hence the Chinese signboard.

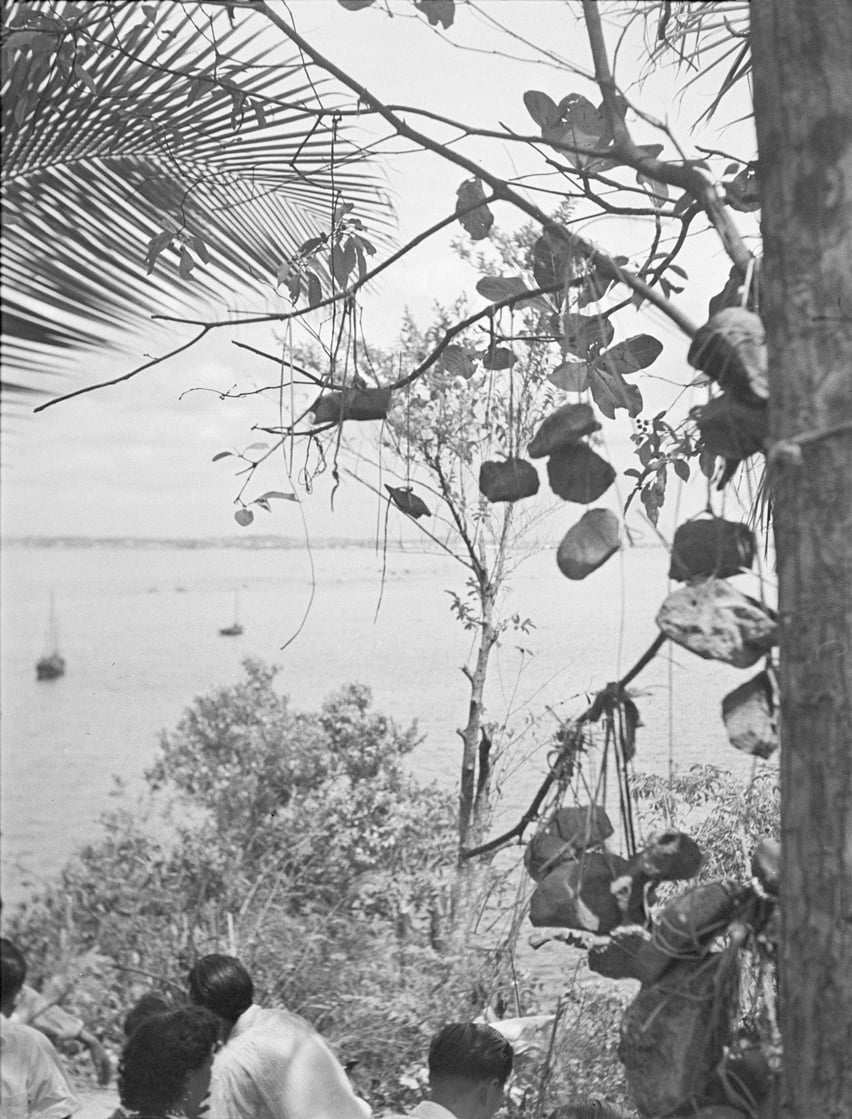

You may notice the hanging stones. Devotees used to tie stones collected from the top of the hill to tree branches and even the top of the shrines themselves, believing that the higher they tied the stones, the more likely their wishes to Datok Kong would come true.

Credit: N.53979.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Credit: T.54774.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Out of the five siblings who formed the fourth generation of caretakers of the keramat, Pak Besar, the eldest, was in charge of the Datok Kong shrine.

Pak Besar is the older man in the songkok, second from left in T.54774.ELT. The man in the white headband in T.54778.ELT is Samad, elder son of Pak Besar. The younger man in the songkok, crouching down in T.54778.ELT, is Majid, the younger son.

The crumpled newspapers on the floor contain food offerings by the devotees. Some of these offerings included tobacco and betel leaves.

Credit: T.54778.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Credit: N.53980.ELT, MAA Cambridge

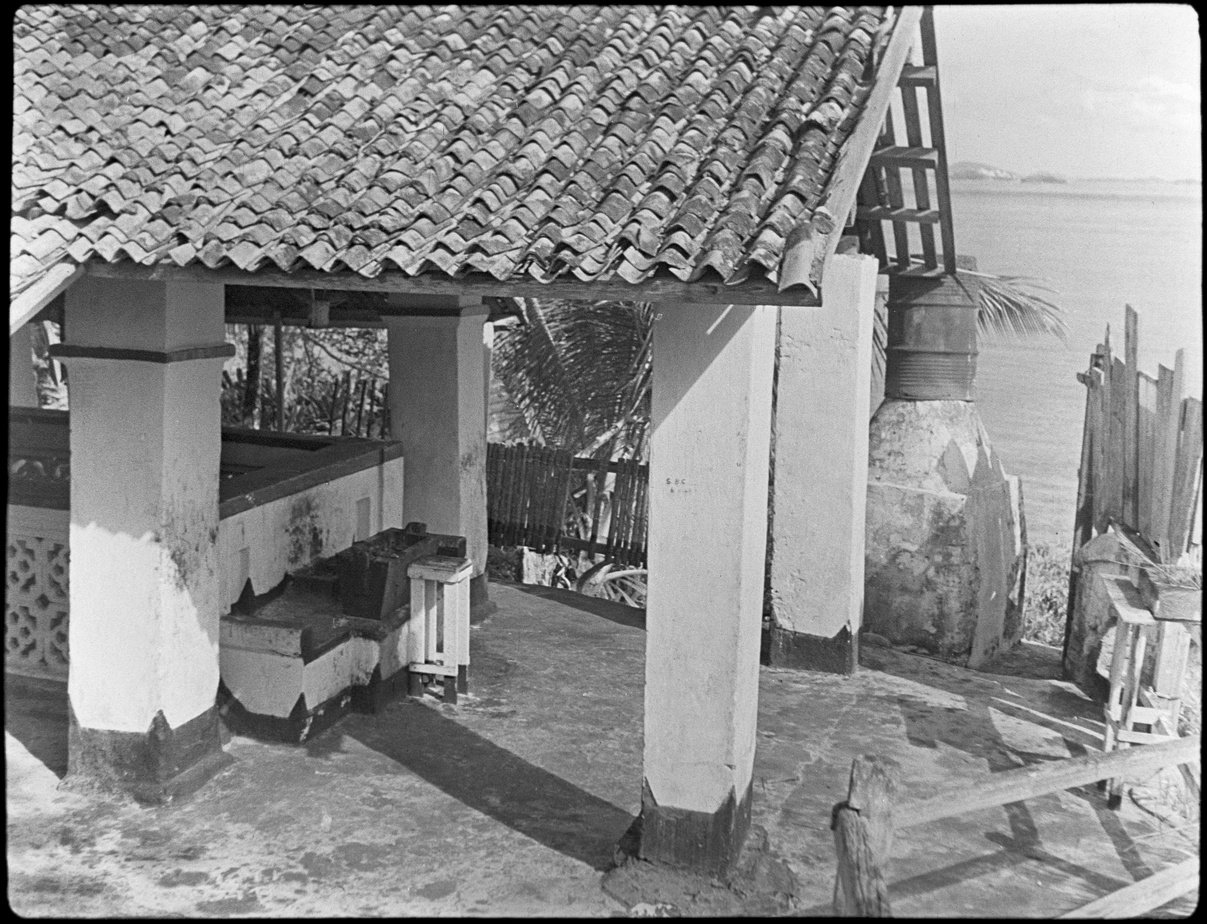

Side view of the Datok Kong shrine. The furnace for burning joss paper is affixed with an oil drum to act as a chimney. The original cement furnace is still in use today.

Side view of Nenek Ghalib and Puteri Sharifah Fatimah’s shrines. On particularly crowded days like this, devotees often stuck their joss sticks haphazardly around the hilltop, causing mini fires that the caretakers had to put out almost every weekend of the pilgrimage season.

Credit: T.54782.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Credit: N.54294.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Offerings in a corner of Nenek Ghalib’s shrine. In the top right corner, a piece of cloth wraps around a tree trunk. This tree is the sacred tree which housed Nenek’s spirit.

In the 1800s, a tycoon Hong Lim came with his wife to pray to the tallest tree on the top of the hill, wishing to be blessed with children. When his wish came true, he subsequently financed the construction of the shrine around the sacred tree.

After the tree died, some devotees continued to believe in its enduring healing properties. They would request for the caretakers to shave off parts of the tree bark for them to bring home, grind up, and make into a paste to apply on the skin, a cure for skin diseases.

Credit: N.54293.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Puteri Sharifah Fatimah’s shrine. The man in the white headband is Husein, the youngest son of Dara. Dara was the younger sister of Pak Besar and the third eldest sibling, and she was in charge of Nenek Ghalib’s shrine.

Credit: N.54280.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Credit: N.54281.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Stones tied to tree branches at the top of the hill, by devotees hoping to strengthen their wishes to the deity. The practice of tying stones ended in the 1970s, when pilgrims were discouraged from doing so on the grounds of safety. Nowadays, devotees write their wishes on yellow ribbons and tie these to the tree branches instead.

View of the Tua Pek Kong temple from the keramat. The function of the structure in the foreground is unknown to the caretakers, though one might notice that the paint design at the base of the pillars is the same as that of the Datok Kong shrine.

The colour scheme of the shrines and this mysterious building was yellow and dark green. Yellow is a symbolic colour in Malay culture, associated with royalty. Datok Kong shrines in Singapore are typically painted yellow.

Credit: N.53982.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Devotees climbing the staircase up to the keramat. A woman in the bottom right holds a bunch of black joss sticks, which were the main type of joss sticks offered at the keramat in the 1950s.

The more common Chinese red joss sticks came to be in use after the 1950s, after the caretakers received feedback from devotees that they preferred using those.

Credit: N.54283.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Credit: N.54289.ELT, MAA Cambridge

View of the keramat from the temple. People ascend the hill on the left, making their way up the muddy terrain, their footsteps paving natural ‘stairs’ in the hill.

Credit: N.54282.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Bumboats and sampans in the waters at medium-high tide, ferrying people between the keramat and the temple.

Land reclamation in the 1970s subsequently connected the temple to the keramat.

Credit: N.54284.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Credit: N.54285.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Credit: T.54775.ELT, MAA Cambridge

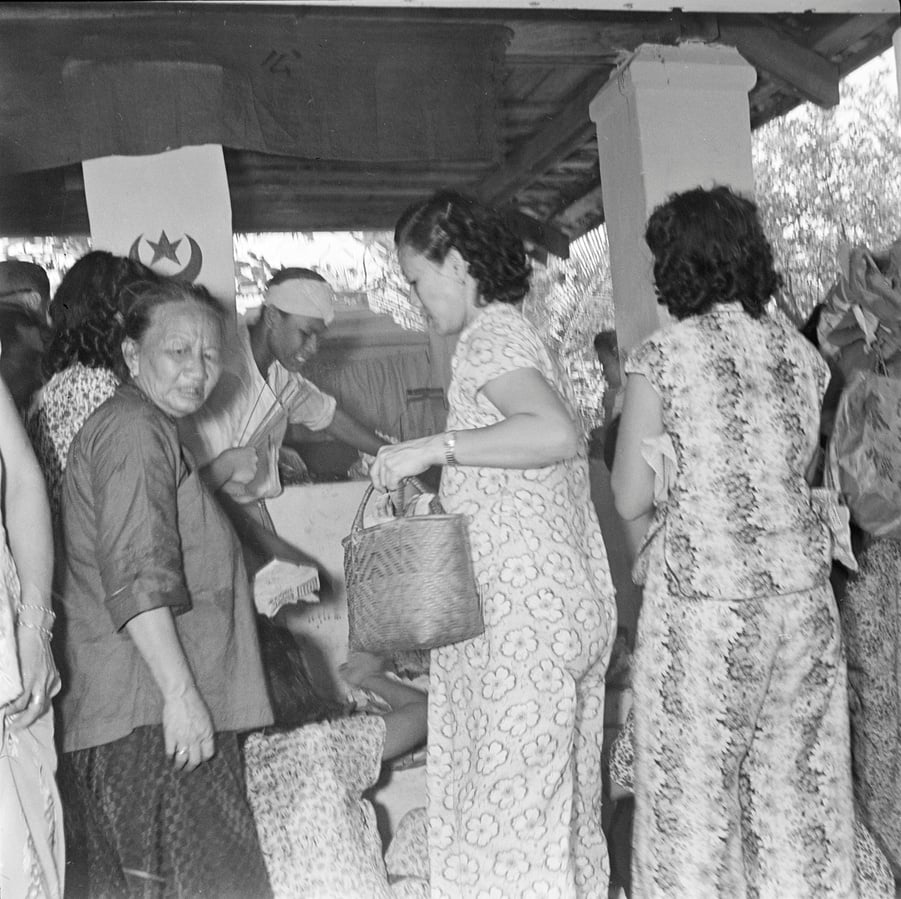

Hawker stalls on Kusu Island set up under attap roofs. The stall in N.54291.ELT is selling beehoon and other dishes.

It was common for Kusu Island hawkers to sell Chinese food to cater to the predominantly Chinese crowd during the pilgrimage season, but they would exclude pork and lard from their cooking to respect Datok Kong.

Hawkers were not allowed to sell joss sticks and flowers, as those were sold by the keramat and temple caretakers.

Credit: N.54291.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Credit: T.54776.ELT, MAA Cambridge

Hawkers selling corals near the temple. Villagers from Pulau Sekijang Pelepah and Pulau Sekijang Bendera would harvest the corals, bury them in the sand for at least one year to naturally bleach them, and bring them over to Kusu Island during the pilgrimage season to sell to pilgrims as decorative pieces.

Credit: T.54783.ELT, MAA Cambridge

The practice of harvesting and selling corals ended around the 1970s when the villagers were resettled onto the mainland, and land reclamation in the southern islands smothered most of the coral reefs.